The author of this article was a member of the working group commissioned by the then Ministry of Public Administration and Justice in 2012/13 to produce a planning document summarising its recommendations for Hungarian government relations with the BRICS countries. At our very first meeting, we concluded that these countries differed so markedly, even in terms of their geopolitical positions, constitutional and social principles or their relationships to the existing world order, that it was difficult to imagine their deeper cooperation based on trust in the foreseeable future. Moreover, the prospect of their integration in any likeness to the European Union or NATO is not worth considering.

But this is not to say that the BRICS should be underestimated—a mistake by those Western journalists who have highlighted only their weaknesses. After all, each participant is a major player in the international system (albeit not of equal weight), and, for all the limited scope of their cooperation, they rely on each other to pursue their interests, and thus have a major impact. The most important question is therefore what role we actually attribute to the intergovernmental organization known after its enlargement as BRICS+ in the changing world order of our time.

What is BRICS Actually?

Rarely mentioned nowadays, the term BRIC itself (formerly without the S for the Republic of South Africa) was originally coined in 2001 by the multinational investment bank Goldman Sachs Group to describe the largest and most promising emerging economies, rather than by the group of countries concerned. When the consultative and co-operation forum of these countries was set up, they actually adopted this catchy name with several possible interpretations. The memory of the previous attempts at organized cooperation between Russia, India, and China was also lost in the background. These had been initiated by Moscow at the turn of the millennium, with the obvious aim of bringing the three major Asian powers together to limit US influence on the continent. However, the Indians did not want to participate in a cooperation that would have required them to coordinate their security policy too closely with China, which they still regarded as a potential enemy, and would have pitted them against the US, with which they hoped to build up fruitful relations. In contrast to Beijing and Moscow, New Delhi did not see the leading role of the USA in the world as a threat, and rapidly developed its cooperation with it after the turn of the millennium. Without India, the second largest emerging power, it would have made little sense to think of a coalition that sought to represent the interests of states outside the “collective West” in shaping the world order by limiting it in some way.

Finally, BRIC (BRICS from 2010) was formally established at the level of foreign ministers in 2006 and then at the 2009 summit, and it adopted quite a different framework of interpretation. Its mission could be defined not against someone/something but for something, it was not limited to Asia, and its objectives were economic rather than security policy. It could thus be integrated into a system of objectives and instruments of an Indian foreign policy that saw the preservation of strategic autonomy as a primary interest, and sought to negotiate with the world’s often divergent centres of power by developing the country’s relations in a number of directions. By the early 2010s, China and Russia, on the other hand, had seen the time was ripe to weaken the influence of Western-led institutions, taking into account even Indian sensitivities, which focused on modernization needs. Accordingly, a key objective of the BRICS group was to develop their trade between themselves, the “major non-Western economies”, to encourage mutual investment and to offer an alternative to Western-dominated international financial institutions. In this context, there is also a concern to represent the interests of the wider international community, which dovetails particularly well with India’s gestures of solidarity with the states of the Global South. It also provided an opportunity for the Russian and the Chinese sides to increase their acceptance among countries that had reservations about their foreign policy by strengthening business ties.

In a move to at least partially decouple from Western-dominated financial institutions, the parties set up BRICS’ own investment bank, the Shanghai-based New Development Bank (NDB) in 2015, which provides loans for infrastructure development. While all UN member states can participate, the original BRICS voting share is not to fall below fifty-five percent. This is to ensure that the bank does not come under the influence of a country outside the original group. The very existence of the NDB affects market conditions, as clients of the former institutions can now seek development loans elsewhere.

In addition to economic projects, BRICS can also play a positive role in the world of diplomacy. Its annual summits are important fora where leaders can discuss their differences separately on the margins of the official agenda. This has proved particularly useful in the India–China context, but, as the group expands, it could also serve well in other relations (e.g. Egypt–Ethiopia, Indonesia–China, etc.).

Since 2017, work has accelerated on a major expansion of the organization, in line with BRICS’ stated vision to represent a wider range of states. Egypt, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, and Ethiopia became members on 1 January 2024, followed by Indonesia on 6 January 2025. However, Argentina, whose accession was also scheduled for January 2024, withdrew, referring to its stronger value orientation towards the West as its reason to do so.

And What it is Not?

Along with its disparagement, BRICS is often interpreted by journalists as the beginnings of some kind of anti-Western bloc. According to this view, the very existence of the group is itself evidence of the decline of the West, a bloc of emerging powers challenging Western institutions and a serious risk to the future of Western societies. In support of this view, authors often resort to old-hat hyperbole: they add up the various indicators (population, GDP, armed forces, etc.) of the member states as if they were one state. If this is done, BRICS+ looks like a very impressive force indeed. Its aggregate GDP may be slightly higher than that of the G7, its military strength far exceeds that of the US, its population is roughly forty-six per cent of humanity. But these reflections suggest, often unintentionally, that the grouping is an integration or at least a close alliance of states, perfectly united in the pursuit of a common will.

But this is not the case. BRICS+ is an intergovernmental organization whose objectives do not include any integration, and any decisions it takes requires consensus among its members (not to mention that implementation is also very much dependent on the political will of the individual states). In discussions with experts from the countries concerned, it is often pointed out that they do not really understand why the West wants to compare BRICS with their own integration organizations. BRICS+ cannot be likened to NATO and the EU with their wholly different objectives, effectiveness, and perspectives. Not least because BRICS+ has very few common achievements, and the prospects of their further development are uncertain. Moreover, 2024 has shown the limits of economic cooperation. The plan to replace the US dollar with a BRICS currency in trade between member states has provoked Washington’s strong response. Donald Trump’s announcement that he would impose a hundred percent tariff on US imports from member states if this were to happen quickly convinced the Indian government, which has a significant surplus on its foreign trade with the US, that it would not be worth it.

It is also important to note that international organizations with Russian and Chinese membership are often assessed from the perspective of the conflicts of the day, and the unquestionable anti-Westernism of these two great powers is projected on them. However, this is far from being true for the majority of BRICS+ states. Even among the original five, only a minority genuinely felt they had much to gain from a rapid dismantling of the existing world order, while the majority preferred to see gradual change, the achievement of genuine multipolarity, as their longer-term goal. The latter is indubitable not only from a practical point of view but also from a moral one, as it would in fact ensure a more balanced development of international relations.

A More Powerful Coalition?

With Indonesia’s accession in January 2025, the original membership of BRICS has doubled. Whether this is a move towards strengthening or a move towards containment depends largely on the perspective of the respondent. If we follow the practice of adding up economic/military/social indicators, BRICS has indeed grown much with the addition of new members. The accession of the leading economic power in Southeast Asia can also be said to have greatly improved its geographical coverage.

However, in the context of the enlargement of a consensus-based organization, the inclusion of new members with very different aspirations significantly reduces the effectiveness of decision-making, as there will be fewer issues that are seen as common interests by all members. For example, Indonesia, which, like India, is a balanced, sovereign strategic thinker, has admittedly joined the organization to increase its international visibility, which it sees as just one of many fora in which it can express its views on issues on the world political agenda. More generally, it is also true today that BRICS+ does not really have any member states that prioritize the development of the organization over their own narrow geopolitical interests. There is still potential for the development of mutual trade relations, but it is worth considering that the member states are far from equal in terms of economic performance. In 2023, a little more than half of BRICS’ combined GDP in nominal terms was generated by China, and roughly twenty percent by India. The others shared the remaining roughly thirty percent, and the internal ratios have not become significantly more balanced with the addition of new members. And India is one of the powers with the least interest in further increasing China's economic influence in the world.

All in all, BRICS is a remarkable initiative (and its members want it to be), whose survival is also fostered by expectations of a transformation of the world order and the desire of individual states to position themselves in it. Ignoring it is therefore as flawed as overstating its import.

The author is a historian, political scientist, security policy expert and fellow at the John Lukacs Institute of Ludovika University, Budapest

Translated by Péter Pásztor

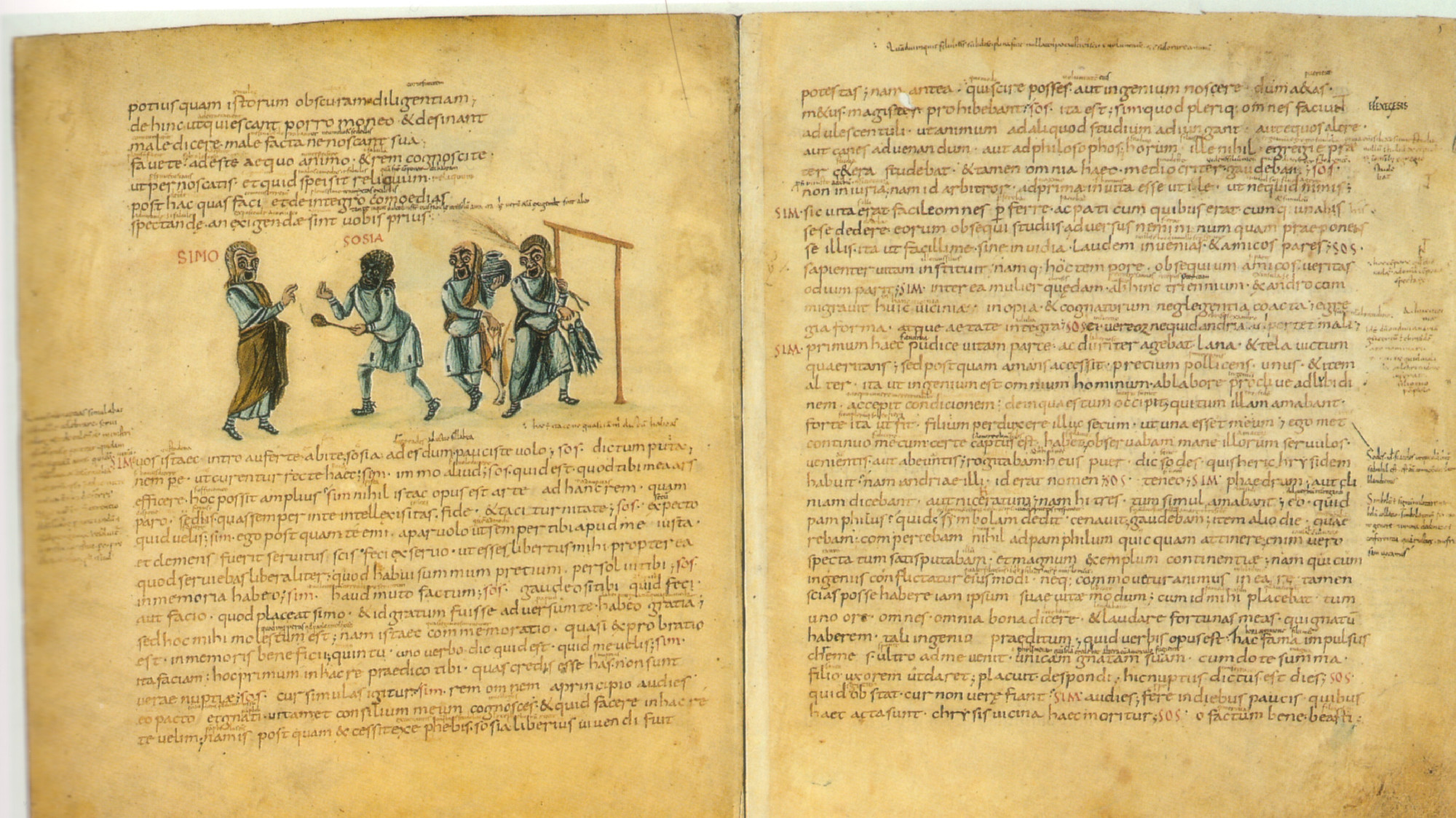

Cover photo: The 16th BRICS Summit in the Outreach/BRICS+ format in Kazan, Russia in 2024