Often dubbed infamous, his signature “malaise speech” not only addressed contemporary challenges but a “crisis of confidence” that he in large part had only inherited from the Kennedy and King assassinations, Vietnam, and Watergate. His foreign policy made an excellent target for his critics despite the fact that he used the same deck of cards his predecessors had left him.

Realpolitik is Dead, Long Live Realpolitik!

Jimmy Carter began to play the hand he was dealt with humility. In his inaugural address, he quoted the prophet Micah: “He hath showed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God” (6:8). The 39th President of the United States infused this admonition into foreign policy. He believed that the essence of American power was not coercive strength but the “nobility of ideas”. Accordingly, he sought to turn away from Henry Kissinger’s Realpolitik. Carter’s main complaint was that the former National Security Advisor (and Secretary of State) focused exclusively on power blocks and spheres of influence, but Carter also condemned the lack of transparency in foreign policy decision-making, namely that Kissinger had been making initiatives without the knowledge of stakeholders in the executive and legislative branches of government. In his speech at the University of Notre-Dame, Carter outlined the new emphases of American conduct: a new focus on human rights, an enhanced alliance with democracies, further reductions in US and Soviet strategic nuclear weapons, more efforts on a lasting peace in the Middle East, and a restraint in international arms sales.

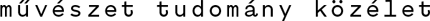

Menahem Begin, Jimmy Carter and Anwar Sadat in secret talks preparing the Camp David Accords signed on 17 September 1978, a major foreign-policy success (photo: CIA, Jimmy Carter Library, Atlanta, GA)

A broadened Détente with Similar Outcomes

Carter’s initial critique of détente was that it gave too much room for the Soviets in Eastern Europe. Throughout his 1976 presidential campaign, he criticized his Republican predecessor for selling out human freedoms and the possibility for more independence in the region. But while Carter highlighted President Gerald Ford’s gaffe that “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and there never will be under a Ford Administration” as well as State Department counselor Helmut Sonnenfeldt’s debated remarks on striving „for an evolution that makes the relationship between the East Europeans and the Soviet Union an organic one”, he was also cautious not to make any specific promise on how he would change course on US policy regarding Eastern Europe. Carter’s National Security Council began a comprehensive review of European matters in February and issued a presidential directive on the policy toward Eastern Europe in September 1977. In essence, the policy called for a distinction between the Eastern bloc countries based on their respective levels of freedom domestically and independence internationally. In accordance with this dual line of thinking, Poland and Romania would “continue to receive preferred treatment with regard to visits by government officials, and in handling economic issues and various exchange programs”, whereas relations with Hungary would “be carefully improved to demonstrate that its position” was similar to Poland and Romania. The rest of the Eastern European countries were not intended to enjoy the political (diplomatic) and economic (trade) advantages of détente as offered by the Carter administration.

Signing the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) II in Vienna with Leonid Brezhnev on 18 June 1979 (photo: Bill Fitz-Patrick, Jimmy Carter Library, Atlanta, GA)

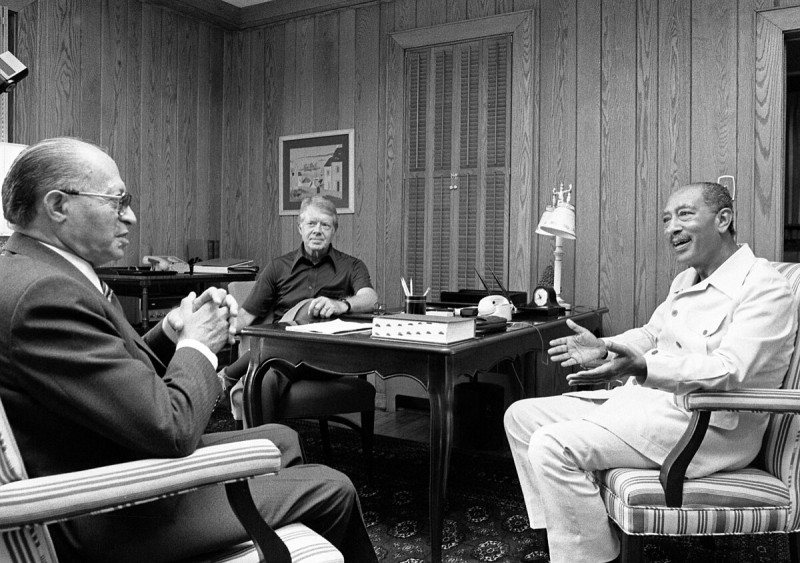

Lining up to see the Crown at the National Museum, Budapest, 1978 (photo: Viktor Gábor/Fortepan)

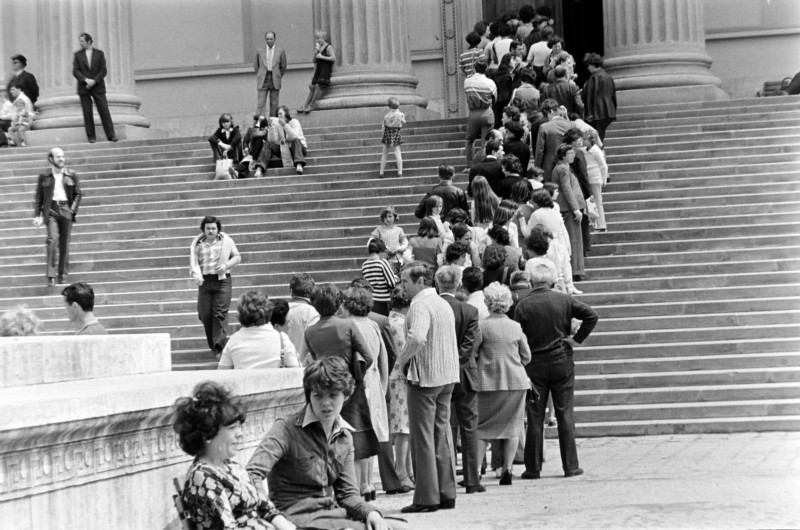

Replica of the Holy Crown of Hungary at the Jimmy Carter Library and Museum, Atlanta, GA

The limits of détente were more apparent in the case of Romania. The Carter administration’s 1978 annual report on Eastern Europe assessed that the country was neglected by the US government. On the one hand, the report acknowledged that “Romania’s human rights record is in need of improvement”, it also noted that the country “clearly demonstrated the greatest degree of independence from the Soviet Union”.

Nicolae Ceaușescu delivering his toast at the White House in April 1978 (Jimmy Carter Library, Atlanta, GA)

In accordance with the initial policy guidelines, Jimmy Carter welcomed Nicolae Ceaușescu in Washington on April 12, 1978, following the footsteps of Nixon and Ford who both met the Romanian dictator on his formal visits to the United States. Thus, as much as Carter broadened détente and emphasized domestic liberties, the hard realities of international politics assured similar outcomes.

The author is a research fellow at the John Lukacs Institute at the Ludovika University, Budapest

Cover photo: Joshua Carter, grandson of President Jimmy Carter, delivers a eulogy during the former president’s state funeral at the Washington National Cathedral, Washington, D.C., 9 January 2025. Carter, the 39th President of the United States and 2002 Nobel Peace Prize recipient for his humanitarian efforts (DoD photo by U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Darien Wright)