Professor Yan set two goals for his lecture: to identify the changes taking place in the international environment and to explain China’s foreign policy strategy through them. In outlining the distinctive features of the international environment, he focused on three main aspects. First, he identified a quasi-bipolar Sino–American international power structure. Although there are several important players in the international order, they are at best only regional powers and their capacities are significantly inferior to those of the two leading superpowers. Yan pointed out that

the US still has a significant advantage over China in terms of capacity, and that trends in recent years suggest that the gap between the two powers is unlikely to close in the near future.

A second striking feature of our times, Yan argues, is that the seemingly unbreakable trend of globalization is also changing: the unity of the world economy is being disrupted by great power rivalries, thanks to protective tariffs, state support for domestic production, and economic warfare. As a result of counter-globalization, a process of forming blocs reminiscent of the Cold War is taking place. Finally, the third major trend today is that we have entered the digital age. Data, the main raw material of digital economic development, is a special resource that is infinite: the more we consume, the more we have. Countries that can use data efficiently can quickly gain an advantage over others. Not surprisingly, the two leading powers are doing their best to outdo each other in this sphere. Professor Yan concluded his assessment by saying that the post-Cold War era is over. In this new period of history, rules and norms have been shaken, which can lead to increasingly unpredictable and abrasive solutions in international relations. He repeatedly reminded the audience that we have entered a dangerous new era.

The second half of his talk focused on China’s foreign policy strategy. But before turning to the Chinese government’s response to the challenges outlined, he delineated the US strategy for the sake of contrast. The primary objective of the United States is to maintain its leadership. It defines China as its major strategic competitor capable of challenging its leadership. Its objective vis-à-vis China is defined by the principle of containment, which is, however, selective. It focuses primarily on the military and technological spheres, but leaves room for cooperation in certain areas (the “small yard, high fence” policy). Its strategy is essentially a repetition of the strategy used during the Cold War, in the hope of winning the new great power competition. The distinctive elements of the strategy are also similar to those of the Cold War period. It is taking material steps to make its own and its allies’ economies independent of China. And, unsurprisingly, ideology will again play a role, albeit it will be a means rather than an end. China, on the other hand, is doing its utmost to avoid a new Cold War, because neither ideological rivalry nor proxy wars support its goals. Yan argued that China’s primary goal is to prevent the widening of the power gap and to transform the geopolitical environment in a way that is favourable to it but far from simple. At least as important for

China is to maintain globalization as a guarantee of the country’s renewal, a central promise of the Chinese Communist Party.

The primary means to this end is the Belt and Road Initiative, through which China offers cooperation to countries wishing to maintain globalization.

Professor Yan’s lecture had an important message for its Hungarian audience. Perhaps the most influential thinker in one of the world’s leading powers agrees with the thesis that the world is entering a new era, one that will be far more unpredictable and dangerous than previous decades. It was also instructive to have a summary of the competing foreign policy strategies of the USA from a Chinese perspective. On the other hand, however, the talk left the listener with a serious sense of want. One had the impression that, although the Chinese leadership is aware of the changing world and the blows it has received from the United States, it has a merely dove-like strategic response to it, as opposed to its previous practice of “warrior-wolf diplomacy”.

The lecture was thus clearly intended to give emphasis to China’s attractive side

and to send a message to the Hungarian audience that China acts as a responsible superpower. It even voiced that qualitative Chinese growth needs Europe, the well-to-do market of which can absorb its added-value and thus more costly products. This was why the listener could not rid herself or himself of the idea that that the Chinese elite must obviously have an alternative plan for the future. The discussion of such alternatives would have better suited one of the best realist political thinkers in the world.

The author is a historian, a fellow of the John Lukacs Institute in Budapest

Translated by Péter Pásztor

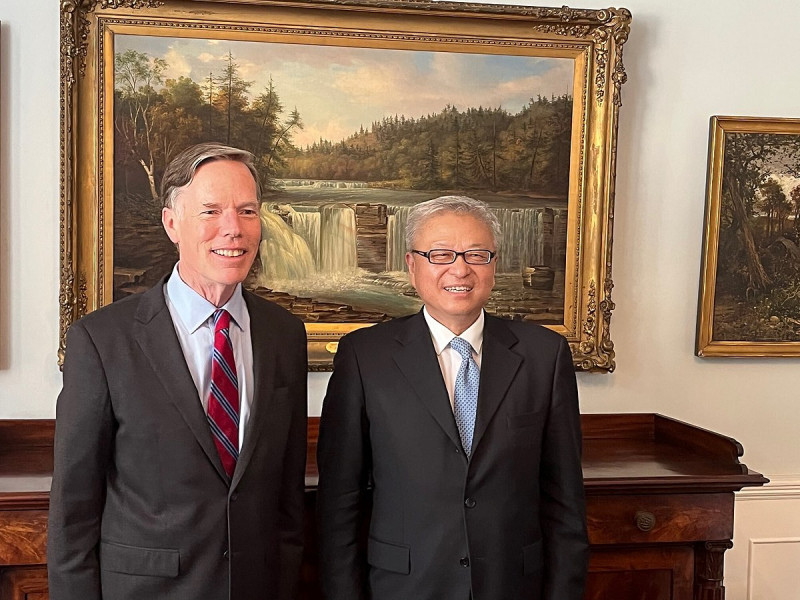

Cover photo: Yan Xuetong speaking at the Danube Institute with his panelists, the author Viktor Eszterhai and Eric Hendriks, a fellow of the Danube Institute